Supporting Children with Anxiety in the Primary Classroom

- Primary

- Education and Language

- Inclusion

- Anxiety

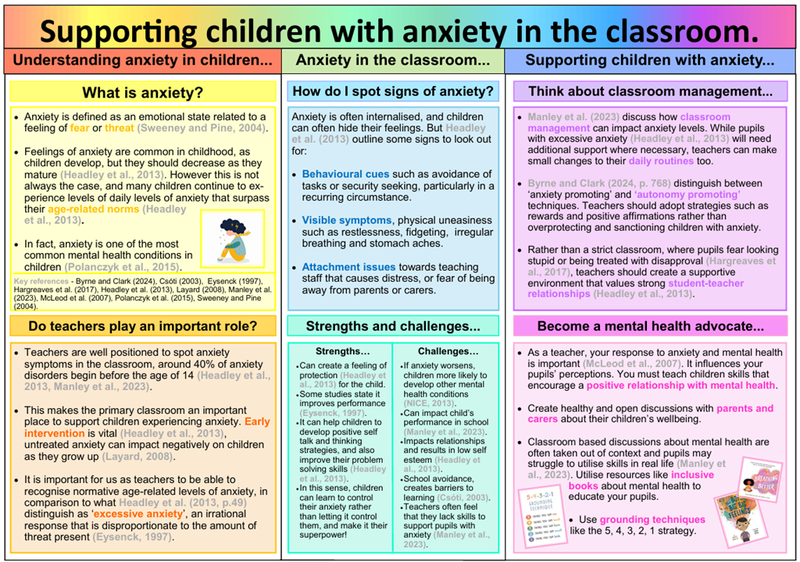

While the poster below summarises anxiety within the primary classroom, this discussion shall elaborate on some key findings. I will divide my discussion into three sections: 1. The prevalence of anxiety in the primary classroom.

2. Strengths and challenges of anxiety.

3. Inclusive strategies to support children with anxiety.

1. The Prevalence of Anxiety in the Primary Classroom

As outlined in the poster, 40% of anxiety conditions develop before the age of fourteen (Manley et al., 2023). In fact, anxiety is the most common mental health issue experienced by children (Headley et al., 2013; Polanczyk et al., 2015). These statistics highlight just how important the primary classroom is for supporting children with their mental health (Manley et al., 2023).

Sweeney and Pine (2004) define anxiety as an emotional state relating to a feeling of fear. But it is important to distinguish between normative levels of anxiety and what Eysenck (1997, p.32) calls ‘excessive anxiety’ (Headley et al., 2013). Anxiety is a natural response to a perceived threat, and it is especially common in children (Headley et al., 2013). However, excessive anxiety occurs when an individual feels unreasonable levels of fear in response to a situation with little or no real threat (Eysenck, 1997). This feeling of fear can become constant, and it can impact an individual’s ability to function day to day (Headley et al., 2013; Manley et al., 2023).

In studies, and in society, anxiety is often referred to as a ‘disorder’ or a ‘problem’. However, this discussion will refrain from using such definitions. Some studies suggest these terms create a stigma which can isolate the individual and ignore the experiences that may contribute to their anxiety (Smail, 2005; Laing, 2010). In terms of inclusive practice, it is important to recognise the personal circumstance of a child and how this might contribute to their anxiety.

2. Strengths and Challenges of Anxiety

Some studies, such as Manley et al. (2023), suggest that excessive anxiety can have an adverse impact on all aspects of a child’s life. Anxiety is often internalised, meaning children hide their feelings and often struggle on their own (Headley et al., 2013). In this sense, there are notable barriers that anxious children might face in the classroom. They are more likely to be absent from school, which can create gaps in learning that may be difficult to address (Last and Strauss, 1990; Csóti, 2003). Also, the more school that an anxious child misses, the more likely they are to perceive school as a threat that triggers their fear response (Csóti, 2003). Even when anxious children do make it into school, they may present avoidance behaviours such as work refusal or disengagement which also impacts their learning (Campbell, 2006). Overall, regardless of how a child’s anxiety presents itself, their learning is likely to be negatively impacted without the correct support (Headley et al., 2013).

Although, Eysenck (1997) found that in some circumstances excessive anxiety can actually improve school performance. A child may push themselves and perform better due to a fear of failure (Eysenck, 1997). However, I would argue this cannot be discussed as a ‘strength’. Concerns arise as to the mental cost at which this academic achievement is attained. As already outlined, the internalising nature of anxiety is perhaps the most dangerous aspect of the condition (Headley et al., 2013). It is important that teachers remain vigilant and aware that anxiety can present itself in different ways for different children. That is why an inclusive approach, which meets individual needs, can be so effective when supporting children with anxiety.

Despite all of this, it is important to not focus solely on the negative outcomes that children with anxiety might face. Headley et al. (2013) suggests that when anxious children are properly supported in school they are more likely to develop positive self-talk strategies that they can utilise in the future. In relation to Social and Emotional Learning (SEL), skills such as mindfulness and self-regulation are important for any child’s future. As NICE (2013) outlines, if anxiety worsens it can increase the chances of a child developing other mental health conditions in the future. Therefore, it is important that children are given the correct support and taught how to create a positive relationship with their mental health (McLeod et al., 2007).

3. Inclusive Educational Strategies

In terms of mental health, school budgets often struggle to stretch to pay for school based interventions such as counselling (Ainscow et al., 2016; Manley et al., 2023). Alongside this, children’s mental health services in England are overwhelmed by rising demand (Thorley, 2016). Therefore, teachers have a key role to play in supporting children with anxiety.

An issue that is highlighted repeatedly in the literature surrounding anxiety in the primary classroom is that teachers feel ill equipped to support anxious children (Headley et al., 2013; Manley et al., 2023). Even though anxiety commonly emerges at primary age (Headley et al., 2013; Polanczyk et al., 2015), Manley et al. (2023) found the majority of teachers lack confidence on the subject.

In response to this, Manley et al. (2023) suggest that altering your daily routines as a teacher is an effective way to support anxious children. By instilling an inclusive classroom ‘culture of opportunity for everyone’ (Cremin and Burnett, 2018, p.138), the teacher can ensure that anxious children are assisted and able to access the curriculum fully (DfE, 2013). For example, during my SE1 placement, I observed how the teacher set up a ‘mindfulness minute’ each day. Pupils were given time to self-regulate their emotions, and the teacher encouraged the class to share positive affirmations with their peers. This strategy allowed everyone, but especially the anxious children within the class, to relax and feel comfortable in the classroom ready to learn.

In relation to this, Byrne and Clark (2024, p.768) distinguish between ‘anxiety promoting’ and ‘autonomy promoting’ responses in the classroom. Some classrooms can be strict and authoritarian. This behaviourist-style approach, in which pupils take a passive role and are expected to absorb information from their teacher, is anxiety producing for pupils (Hargreaves et al., 2017; Byrne and Clark, 2024). Children are scared to put forward answers or be involved in learning due to a fear of being told off. Instead, teachers should aim to create an inclusive environment that lacks hierarchy (Cremin and Burnett, 2018). Daily routines should promote pupil autonomy, valuing encouragement and improving problem solving skills (Byrne and Clark, 2024). I witnessed the implementation of this approach to support an anxious child during my inclusion placement. Children were invited to share their thoughts in lessons, and the teacher ensured that children were supportive with their peers’ ideas. As a result, classroom engagement was good. But also, a particularly anxious child began to feel more at ease when coming into the classroom.

Overall, this assignment has allowed me to develop a deeper understanding of the meaning of ‘inclusion’ within the primary classroom. I have discussed the topic through a focus on the NC (DfE, 2013), which has helped me to grasp the importance of setting high expectations and removing the barriers to learning that individual children might face. Through the analysis of relevant academic literature and reflecting upon my own placement experiences, I feel much more confident as a teaching in training approaching the idea of inclusion. I feel well equipped to be able to implement inclusive strategies such as dialogic teaching (Alexander, 2008), the correct use of groupings and creating a curriculum representative of my pupils’ experiences. Going forward I plan to make scaffolding a pivotal part of my planning process, in order to ensure all children can access the same curriculum. I will also be mindful when utilising additional adult support within the classroom, this will guarantee that pupils are not disadvantaged by being distanced from the main learning objective and success criteria of the lesson. As a teacher, it is important to remember that a single class is made up of up to thirty individuals with a variety of different life experiences. It is important that the classroom is an inclusive space for this diversity. In terms of my professional development, I want to create a culture based on equity and diversity in my future classroom. I now know from my research just how important inclusive educational strategies can be for learning outcomes in the primary setting.