Supporting EAL learners in the primary classroom

- English as an additional language EAL

- Primary

- Education and Language

- Inclusion

This assignment explores inclusive education in the context of a primary classroom. While examining the scope and purpose of this assignment, I remembered my youth – when I did not speak any English. My very first exposure to English began at age eight, when I was sent to an international school; English was an ‘additional’ language that I had to master for my academic success. My journey as an English as an Additional Language (EAL) student has never been easy, but it is something I cherish and celebrate. EAL is a part of my life; a topic I am passionate about as I strive to become an inclusive practitioner – so that future generations of EAL students coming from a diverse range of households would find themselves welcomed, appreciated and supported in their classroom.

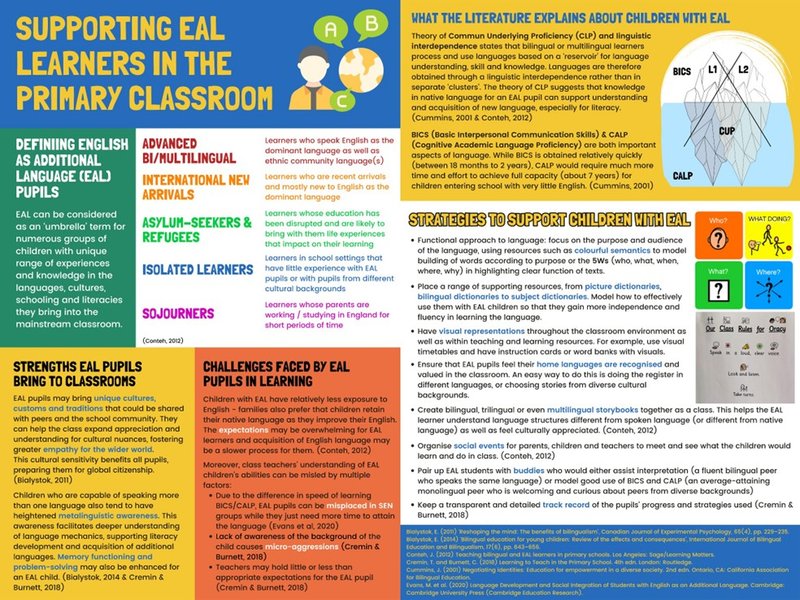

A pupil is defined by the DfE (2020) to have EAL if they are exposed to a language ‘known or believed to be other than English’ at home. It states that the term EAL is not a direct indicator for English proficiency or ‘recent immigration’ (DfE, 2020). Conteh (2012) expands on the definition of EAL into a much more diverse complexity, including the culture and experiences EAL pupils would bring inseparable to their language abilities. Integrating these are essential, as (1) language is a key part of a child’s life as well as a mode of communication; and (2) cultural diversity of EAL children is their strength and potential for the whole school community which receives them. EAL pupils often would have strength stemming from their proficiency in multiple languages with a ‘reservoir’ (Cummins, 2001) of ‘linguistic repertoires’ (Liu & Evans, 2016). For instance, in families that use two or more languages, ‘translanguaging’ is a natural and accepted form of conversation (Cremin & Burnett, 2018) and showcases the heightened linguistic awareness the EAL pupils possess.

With the diverse range of cases present when considering pupils with EAL, there could be a multitude of challenges. One significant challenge is the expectations towards the child from different people around them which may be explicit or subtly implied. It is common with families that are monolingual to want their children to acquire the English language and gain fluency – while maintaining their native language (L1) simultaneously (Conteh, 2012). At a parent-teacher meeting at school A, I met one parent who brought their child to the meeting as the translator – to discuss her own school life. This could be an expectation parents pose on the child who is still in the progress of learning the language. The child may feel discomfort as well hearing about herself then having to repeat it in front of the teacher.

A more subtle, implied expectation on language choice is often placed on the EAL pupil in school by teachers and peers. Since language is closely linked to identity, EAL learners may feel ‘conflicting’ and ‘imposed’ expectations to speak English to ‘fit in’; defined as ‘ascribed identity’, this notion is often present in the EAL learner’s mind to hide the home language identity, or any minority identity they bring (Evans et al., 2020). Also, learning another language is a lengthy process; about seven years is required in achieving full capacity of cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP), in contrast to being able to speak the language colloquially (Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills – BICS) (Cummin, 2001). Teachers who are not familiar with this process may misplace the pupil in SEN groups, or hold lower expectations for the child based on their assessment record and fail to recognise and challenge the child’s full potential. They may even believe that the child should only be encouraged to speak English for faster learning of the language, which again enforces an ascribed identity and incorrectly teaches the child that their L1 is subordinate to English.

The literature as well as the placement schools I saw provided great strategies to support pupils with EAL, based on the strengths the children had. Evans et al. (2020) suggests that instead of singling out EAL pupils, teachers should view their challenges as things any pupil could have regardless of their linguistic backgrounds. The change in perception would de-label the EAL pupil, encouraging the teacher to consider more discreet and sensitive strategies to support the child in a whole-class context as they are not ‘special’. In school A, using visual representations for timetables, instructions and keywords was one such strategy. It was for the use of all pupils in class, yet had massive impact in helping EAL pupils understand the lesson context accurately.

Another strategy is to use L1 of the pupil as a bridge to learn English (Cremin & Burnett, 2018). There is no doubt that gaining proficiency in English is in the best interest of the child living in the United Kingdom; and using L1 as a collaborative tool is maximising the benefits from the pupil’s linguistic strength. Creating bilingual materials together with everyone’s language represented is a simple way of helping EAL pupils learn about the linguistic structure and relationship between L1 and English (Conteh, 2012 and Evans et al., 2020). In addition, this activity would develop awareness and appreciation of the diverse languages and cultures in the wider world we live in for the whole class, benefitting all pupils (Cremin & Burnett, 2018). Similarly, teachers can de-stigmatise the use of L1 in and out of classrooms; valuing the diversity EAL pupils bring in as an ‘asset’ and a chance to create an inclusive learning environment (Evans et al., 2020).

Throughout this essay, I have analysed what creating an inclusive primary classroom entails. The essay commenced with a focus on supporting EAL pupils, discussing their strengths and barriers as well as approaches to support them. I then explored how inclusion would be constructed and embedded and what responsibilities I should uphold as a primary educator. This process involved research into literature and reflection on my placement school experiences. I learnt that the meaning of inclusion in a classroom is to shape an environment where every child feels comfortable in their own shoes; in accessing the curriculum; confident that they are the active learners of their own learning. While being mindful of pupils who would have protected characteristics such as SEND, teachers also ought to understand that supporting them is not separate from supporting a mainstream classroom. An inclusive teacher understands that this is more the reason why the mainstream lesson should become more universally accessible – the purpose of a teacher would be to ensure equity by investigating each pupil in the class and build suitable scaffolds that makes the learning universal.

This assignment was an invaluable opportunity for me to understand the core meaning of inclusion, away from plainly learning a list of adaptations and adjustment strategies to really considering how to root inclusive practice in the curriculum and in the classroom. In my upcoming placements, I will utilise my learning in my teaching, from creating universally accessible lessons in daily and weekly plannings to promoting inclusion in my interaction and communication with the children. I will strive to empower my pupils, listening to their voices as much as possible. I would always remind myself that an inclusive environment is a collaborative effort, where myself, the children and all the other adults in the class work together.