Supporting children with dyspraxia in the classroom

- Primary

- Education and Language

- Inclusion

- Dyspraxia

I chose to focus on dyspraxia for my poster as I came across children who had a diagnosis on my inclusion placement, and I had little prior knowledge about the barriers to learning that children with dyspraxia could potentially face. By choosing a disability I was less familiar with, I have broadened my own knowledge on strategies and inclusive practices I can employ in my own classroom.

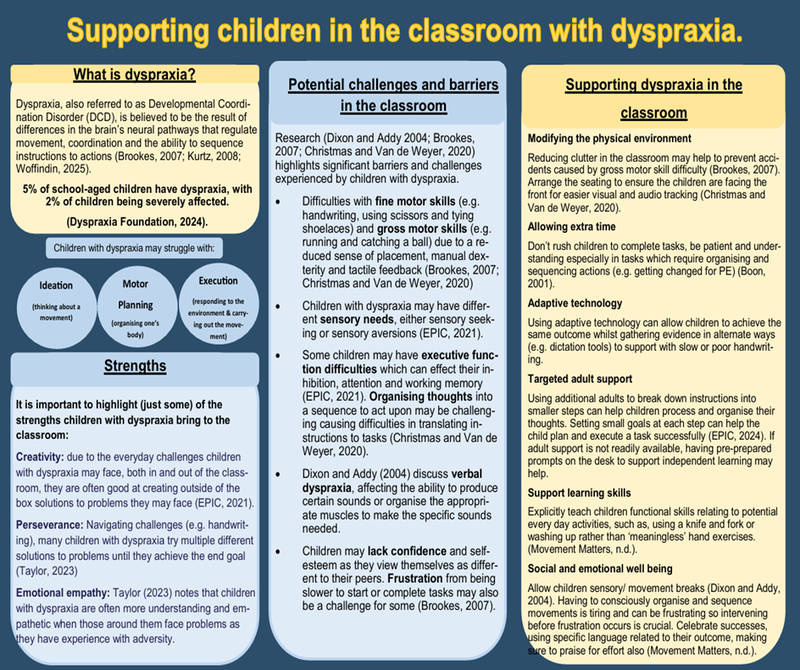

What is dyspraxia?

The origin of the word dyspraxia, often cited in the literature, helps in understanding the diagnosis (Boon, 2001; Brookes, 2007). The root ‘praxis’, Brookes (2007) explained is Greek for doing and acting, which when accompanied with the prefix ‘dys’ can form the understanding difficulty doing or completing an act. Dyspraxia affects a person’s ability to perform coordinated movements as there is a disruption of neural pathways that are necessary for turning instructions into a sequence of actions (Boon, 2001; Brookes, 2007). Although some literature provides the root of the word, or multiple thoughts from the perspectives of different professions on what it is (Boon, 2001), Kurtz (2008) noted that the cause of dyspraxia was yet to be fully understood, and it was simply believed to be involving brain related processes involved in motor co-ordination. Movement Matters (n.d.), a research committee dedicated to dyspraxia, state that there is no internationally agreed definition of dyspraxia, it is simply a broad way to refer to a child who has motor difficulties, similar to the Dyspraxia Foundation (n.d.) who determine it is a neurological condition, affecting perception and co-ordination. Therefore, although they are similar, it is important to proceed with some caution when discussing the definition.

The literature on dyspraxia identifies three stages in the brain involved in performing a task (Brookes, 2007; Kurtz 2008; Christmas and Van de Weyer, 2020). Disruptions in the neural pathways of children with dyspraxia may lead to increased difficulty in executing these actions. The first process in the brain related to praxis is ideation, the ability to mentally think about how to perform a motor movement. For children with dyspraxia, a mental act that becomes automatic for others, has to be cognitively worked out each time the motor movement is needed (Christmas and Van de Weyer, 2020). The next cortical process is motor planning which is the capacity to unconsciously organise the body to carry out the actions needed to achieve the goal. Finally, execution which is the ability to respond to environmental inputs and perform movements successfully, this is then refined until it becomes an unconscious process, an aspect children with dyspraxia struggle with (Brookes, 2007). Expanding on this point is crucial, as it offers a clearer understanding of why children struggle with actions or instructions that require sequencing. It also informs my approach as a practitioner, highlighting strategies to best support a child with dyspraxia. One strategy I observed was a practitioner who chunked instructions of independent tasks into small steps for the whole class, whilst also providing a child with dyspraxia prompts on their table to use when they started an independent task. By using high quality teaching the child was able to access the learning alongside their peers with a slight reasonable adjustment.

Potential challenges and barriers in the classroom and how to support them

It is important that children with dyspraxia are not defined by what they find difficult or cannot do. Highlighted within the poster are the many strengths that children with dyspraxia bring to the classroom; including, creativity, perseverance and emotional empathy (EPIC, 2021; Taylor, 2023). All children should be viewed holistically, as it is important to recognise that although dyspraxia affects neural pathways, there are a multitude of different pathways that could be affected, which leads to every child with dyspraxia presenting in a slightly different way with some similarities (Brookes, 2007). As a result, it will be about adaptive teaching and reasonable adjustments that work for the individuals (Dyspraxia Foundation, n.d.).

As mentioned in the poster, tasks that require fine motor skills and gross motor skills may be more challenging for children with dyspraxia (Movement Matters, n.d.). In the classroom, these demands are placed on children constantly throughout the day so appropriate awareness and management is going to be vital as an inclusive practitioner. More specifically, handwriting is focused on heavily throughout a child’s school career; as a statutory requirement a child should be able to ‘write legibly, fluently and with increasing speed’ by the end of KS2 (DfE, 2013, p46). This complex skill, for children with dyspraxia, may be challenging due to the poor tactile feedback they receive from the pencil and reduced body awareness (Boon, 2001; Christmas and Van de Weyer, 2020; Castellucci and Singla, 2024). Awareness is important for a number of reasons including, planning activities where the outcome is not a written piece (adaptive teaching, which benefits others) or using tools like thicker pencils for greater sensory feedback, adaptive technology or sound tiles to support executive function.

Mentioned in the poster is managing the social and emotional well-being of children with dyspraxia. Expanding on this is necessary due to the significance it can have on a child’s school career. The literature on dyspraxia focuses on the notion of being positive and celebrating successes to help reinforce confidence and build on self-esteem (Brookes, 2007 and Movement Matters, 2023). Contrary to simply celebrating the successful end result, is the importance of giving credit for the journey it took to get there as it may have been frustrating (Boon, 2001). On placement, I observed a child with dyspraxia have the option of brain breaks during and after long tasks (especially those with a high level of handwriting or task sequencing involved). This reasonable adjustment helped regulate the child and reduced levels of frustration as they were able to step away from the task at hand.

Focusing on dyspraxia for my poster has increased my understanding of a SEND need I was previously unfamiliar with. Understanding the cortical processes that take place and the neural pathway differences of children with dyspraxia has informed the reasoning behind inclusive practices I can use to scaffold their learning and social emotional wellbeing successfully. This includes adaptive teaching (e.g. chunked instructions, learning outcomes that are not written based and an intentionally laid out classroom) and reasonable adjustments (e.g. prompts on tables, adaptive technology and thicker pencils). By delving deeper into inclusive education as a broader topic, it has equipped me with an appreciation of viewing children holistically to avoid children becoming self-fulfilling prophecies and how to use high-quality first teaching to inform my practice (through formative assessment, flexible grouping and teaching metacognitive strategies). By breaking down my literature review into academic and environmental inclusive practices it has given me awareness that you cannot have one without the other. If children cannot see themselves in your classroom through the curriculum or literature you read, no matter the quality of the teaching, then true inclusion cannot happen.

In order to build on my professional understanding of inclusion it is imperative to keep building on my subject knowledge of SEND. By having the opportunity to go into different schools I have taken note of different displays which celebrate diversity, books, or key figures used in the curriculum that reflect an aspect of the children in the classroom’s identity. Through the perspective of equity my teaching can reinforce fairness in the classroom by incorporating the strategies broken down throughout this essay.