Supporting Children with Autism in the Primary Classroom

- Primary

- Education and Language

- Inclusion

- Autism

- Neurodiversity

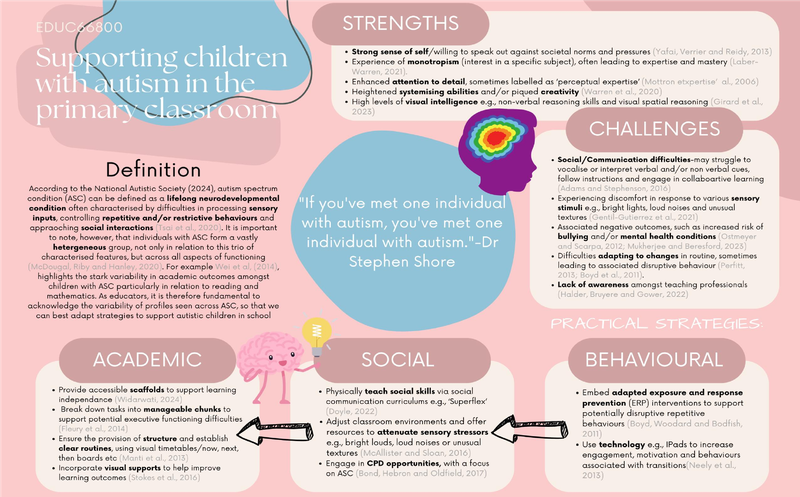

"Autism spectrum condition (ASC) is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition, often characterised by differences in processing sensory inputs, controlling repetitive and/or restrictive behaviours and approaching social interactions (Tsai et al., 2020). Before expanding upon this specific facet of inclusion, it may be valuable first to revisit the heterogeneity associated with not only this trio of features but across all aspects of functioning. Here, we must be prepared to recognise the full variability of profiles associated with a diagnosis of ASC to ensure a truly equitable basis for our future practice (PeterssonBloom & Holmqvist, 2022). The Paradigm Shift: Barrier or Benefit?

When considering the lens through which many professionals perceive a diagnosis of autism, it is essential to acknowledge the framework under which it is regarded. The labelling of autism as a ‘disorder’ within diagnostic manuals like the DSM-5 contributes to a deficitcentric paradigm, reflected across much of the literature (Turnock, Langley and Jones, 2022). Given such biases, it becomes our responsibility as inclusive educators to redefine how autism is conceptualised; when viewed as a disability, autistic traits should be accommodated, but when seen as a neurological difference, autism should be embraced as a unique aspect of human diversity (Cascio, 2018). In line with this thought, I refer to autism as a ‘condition’ rather than a ‘disorder’ to better reflect the heterogeneity of autistic phenotypes, encompassing both barriers and benefits.

Whilst scholarly discourse increasingly champions the adoption of inclusive language, deficit-based perspectives continue to persist in practice, often casting autistic traits in a deleterious light (Cherewick & Matergia, 2023). For example, whilst my poster frames autistic self-advocacy and resistance to societal pressure as an asset, alternative perspectives may favour a deficits-based lens, diminishing the value of non-conformity (Turnock, Langley and Jones, 2022). Similarly, Leekam, Prior and Uljarevic (2011) reject the assertion that monotropism offers significant benefits related to mastery and expertise, instead contending that restricted interests may impede learning and social adaptation. Whilst my poster generally reflects contemporary pedagogical viewpoints endorsing a ‘strengths-based’ approach, it remains fundamental to acknowledge challenges that constitute genuine barriers. For instance, diminishing the perceived urgency surrounding linkages between autism and poor mental health may inadvertently cause harm by hindering access to support systems (Mukherjee and Beresford, 2023). Furthermore, when considering barriers, we must look beyond individual characteristics that may limit curriculum access and instead recognise failings in broader systemic structures (The Key, 2016). Such resourcing challenges are compounded by a perceived inadequacy among professionals, who state that their understanding of ASC is less than optimal for supporting children in the classroom (Roberts and Simpson, 2016). Within the context of my professional development, I, therefore, intend to prioritise engagement with current literature and CPD opportunities to best support children with ASC in my future practice.

Strategies to support children with ASC

Building upon the preceding theoretical discussion of ‘barriers’, it remains important to examine the practical application of strategies that foster meaningful participation and learning. Whilst my poster categorises these into academic, social and behavioural domains, it is worth highlighting the inherent interconnectivity and mutual influence between such aspects. For example, Boyd, Woodward and Bodfish (2011) note the startling link between improved social skills and reduced repetitive behaviours. This, in turn, has further cumulative effects, where a decrease in repetitive behaviours has been shown to improve academic engagement and knowledge acquisition (Muchetti, 2013). Overall, such findings have underscored the necessity of adopting a holistic approach within my practice; to consider only the academic goals of a child with autism is to forget the true interconnectedness of all developmental domains.

Analogous to examining factors beyond the individual child in the assessment of learning barriers, it is important also to consider strategies which support parties beyond a child with ASC. For instance, Critchley et al, (2021) explore how parents and neurotypical siblings of children with autism struggle with problems relating to wellbeing and support. As professionals with ‘expertise’ in this area, we can therefore play an instrumental role in supporting families to offer consistency between the home and school (Minke et al., 2014). "

Whilst the practicalities of its implementation may be complex, inclusive practice exists not only as something to be desired, but as a foundational cornerstone upon which equitable education is built. Through my placement experience and research thus far, I can now see how this commitment to inclusivity should inform all areas of our pedagogical approach, from the very terminology we adopt (e.g., recognising autism as a condition rather than a disorder, thereby challenging deficit-based paradigms), to refraining from grouping children based on pre-perceived biases linked to their SEND status, demographic, or socioeconomic position. Furthermore, by embodying a definitive ‘strengths-based approach’, we can ensure that students not only access the support they need but are empowered to celebrate their unique abilities and perspectives, aligning with the National Curriculum's mandate to "set high expectations for every child” (DfE, 2013). Within the context of my professional development, my understanding of inclusive practice has evolved significantly during this assignment and the corresponding placement experiences, leading to a deeper reflection of my own pedagogical approach. I now recognize for example, that a truly inclusive pedagogy requires more than just good intentions; it demands a critical examination of our own assumptions, a commitment to ongoing professional development, and a willingness to challenge the very systems that inadvertently perpetuate exclusion. As such, stepping into my next placement, I am committed to actively applying these insights wherever possible. For example, drawing on research by Sherrington & Caviglioli, (2020), I aim to utilise scaffolding more effectively during my next placement to ensure that all children can achieve ‘ambitious learning goals’, avoiding the limitations inherent in some differentiated practices. Furthermore, I will continue to establish positive working relationships with specialist staff members such as the SENDCo, to foster an appropriate support system for myself as I work to address any gaps in my knowledge regarding inclusive practice.