Summaries

Investigating the effectiveness of using the video-mediated flipped classroom to enhance student engagement in the IELTS speaking and writing classroom.

- Student Engagement

- Mixed Methods research

- Digital

- Observation

- Flipped Classroom (FC)

- Foreign Language Learning

A great number of Chinese students continue to speak mute English and struggle to write in English after learning this language for many years. The reasons for the poor productive skills are suggested to be related to insufficient practice in the classroom and limited opportunities to use them in everyday life. Research has shown FC may be able to improve students’ language skills by increasing their engagement with learning both in and outside of the classroom. This research aims to investigate the effectiveness of FC in enhancing student engagement and their attitudes towards this mode of learning in IELTS speaking and writing classes in the Chinese higher education context. A mixed research method including observations, questionnaires, and semi-structured interviews was utilised to obtain data from the teacher’s and students’ perspectives. After triangulating the data obtained from observing 15 students and their responses from 13 questionnaires and 11 semi-structured interviews in both the IELTS speaking and writing classes, the findings of this research show FC can enhance student emotional and social engagement, and students perceive positive attitudes towards this mode of learning. But more research is needed to further understand whether FC can enhance student behaviour and cognitive engagement.

The results indicate FC is able to enhance student learning time outside of the classroom; the time for group work, class discussions, practice, and feedback in class is also increased, which is likely to enhance learning effects.

It’s time to talk: a case study investigation into teacher views on CPD in the teaching of English, across a range of career points.

- Interview

- Teacher

- Survey

- Mainstream

- Education

- Teaching and learning

- Education and Language

- Perspectives

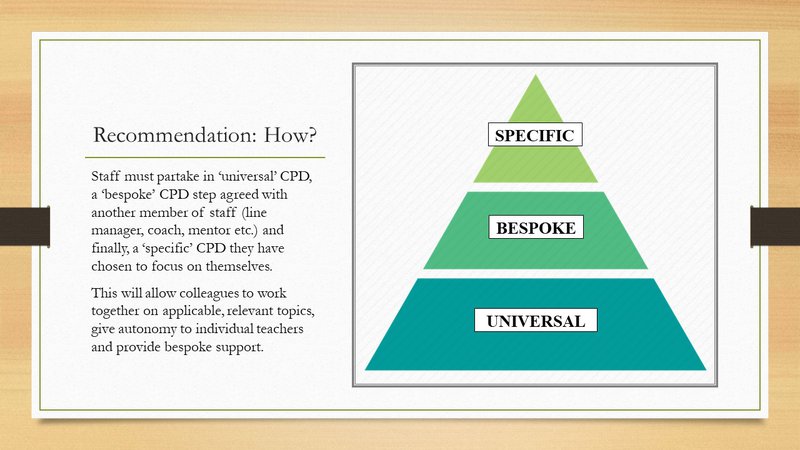

The consensus that CPD is key to school reform means that it is necessary to investigate teacher experiences of and attitudes towards CPD. The definition of CPD is contested in the field, and there are debates as to whether it should be evidence-based, internal or external to the school, time-rich or time-poor, and if it really improves student outcomes. Despite these conflicts, research reveals that teachers of all career stages are rarely asked about their views on CPD even though they are the participants of it. Therefore, this thesis presents the findings of a pilot case study (undertaken within approximately 7 months by a researcher-practitioner in a North-West England academy) of 8 purposively sampled participants which assesses how teachers of all career stages feel towards the CPD they experience as part of their professional work. After thematically analysing data generated generating through questionnaires and interview, the study reveals that teachers have varying, inconsistent CPD experiences. Nonetheless, teachers view CPD as a vital tool to improve as a professional and their desire for good CPD rarely wavers across career stages. Teachers admit to external influences like time and psychological pressures impacting their attitudes towards CPD, but still viewed CPD as something which can, and should, benefit them. Teachers seemed to value colleague-to-colleague support above all else – even their strong desire for CPD that helps them achieve day-to-day tasks. This suggests that all teachers should have a mentor/coach style support, allowing colleagues to support and challenge each other to create the best CPD. The disparities between teachers at different career stages also revealed that CPD should be monitored across one’s career, allowing it to shift to cater to individual, ever-changing needs. Ultimately, the study reveals that to become the best practitioners, teachers need bespoke CPD that caters to individual needs.

Visual depiction of impact is provided:

LGBTQ+ provision in UK secondary schools: A qualitative exploration into teachers’ perceptions of the microaggressions experienced by LGBTQ+ students

- Qualitative

- Teacher

- LGBTQ+

- Student

- Education and Language

- Perspectives

This research aimed to explore teachers’ perceptions and understanding of microaggressions, targeted towards LGBTQ+ students. Microaggressions are behaviours that define subtle forms of discrimination, frequently communicating hostile or derogatory beliefs either intentionally or unintentionally (Nadal, 2013; Sue, 2010). Nine teachers were interviewed, sharing their perceptions of the discrimination LGBTQ+ students currently face within UK secondary schools. This involved discussing the types and frequency of discrimination observed by teachers from students towards LGBTQ+ students, whilst also discussing the perceived impacts of these instances on LGBTQ+ students' wellbeing. Teachers were chosen as the target population of this study in order to gain insight into their understanding of LGBTQ+ student experiences within schools, shedding light on the lack of concrete guidance provided within both school policies and teacher training. Teachers were interviewed over Zoom, with interviews lasting around 40 minutes. These interviews were then transcribed and analysed through Thematic Analysis. From the data analysis, the following three themes were uncovered: (1) acknowledgement of heteronormativity, (2) awareness of microaggressions and (3) school support. Heteronormativity refers to the belief that people fall into distinct genders of either male or female, and that this gender aligns with their biological sex; therefore discounting the existence of other gender identities, sexualities and gender roles (Page & Peacock, 2013). Within theme 1, varied awareness of heteronormativity within schools was demonstrated by teachers. Some often acknowledged its prominence by providing examples such as the lack of consideration when grouping students by their sex on a school trip, however failing to selfreflect on their own teaching practices by not recognising potential instances of heteronormativity within their own teaching. Others showed little to no awareness of the term, also failing to recognise the detrimental impacts of a heteronormative environment on LGBTQ+ students. Within this theme, teachers recognised that bisexual and transgender identities are less normalised than heterosexual, gay and lesbian identities, falling in line with existing research. Nevertheless, positive changes in acceptance over time were also recognised by teachers, with discussion often expressing how teachers feel able to be more open about their own sexual and gender identities within schools, in turn leading to more normalisation towards LGBTQ+ identities amongst students throughout schools. Theme 2 found teachers to have a non-conceptualised understanding of microaggressions, however, teachers were able to provide examples of these instances, whilst showing a cohesive understanding of the impact microaggressions can have on students. Nevertheless, a lack of standardisation amongst reactions to anti-LGBTQ+ behaviours was suggested by teachers as they described how they would manage a situation. Theme 3, school support, found that teachers recognise the importance of LGBTQ+ groups in normalising LGBTQ+ identities and providing students with a ‘safe space’ for support. Other positive school influences were found to be school policies, positive student attitudes, students' age and maturity and teachers’ knowledge. All teachers demonstrated a wish for further teacher training in LGBTQ+ support, particularly surrounding terminology and pronouns. Future research into microaggressions from a student’s experience is suggested, whilst research is also needed to understand the reasoning behind school’s lack of engagement with current literature and practical strategies (e.g., Russel et al., 2021) that it provides in further supporting LGBTQ+ students.

Benefiters of this research includes teachers and educational providers as it aims to raise awareness of microaggressions, whilst providing suggestions for how to better support LGBTQ+ students within the heteronormative school environment. Recommendations for legislation and school policies are also suggested by teachers throughout the interviews, as they describe the need for less ambiguity and more practical suggestions for implementing policy into their teaching practices. For example, current training and policy are described as including ‘buzz words’ and ‘umbrella terms’ of inclusion and diversity, whilst failing to provide applicable solutions to students struggling with discrimination from their peers and/or needing support with their own identity. Further teacher training was also found to be needed by all teachers interviewed, with several teachers expressing a wish for more case study training, further providing more applicability to their own teaching practices. Teachers also expressed a wish for teacher training to be provided by individuals with their own experiences of navigating their own LGBTQ+ identity, having their own experiences of antiLGBTQ+ behaviours; thus, making them better able to direct teachers toward the necessary steps that need to be taken to better support students. By targeting LGBTQ+ acceptance and normalisation within secondary schools, this research aims to further promote a culture of inclusion and acceptance towards diversity, prompting societal changes towards increased LGBTQ+ acceptance.

‘Like no one ever talks about it, so you sort of downplay it all’ Young people’s perceptions and emotional experiences of Climate Change Education in the UK.

- Qualitative

- Secondary

- Focus group

- Education and Language

- Perspectives

This project aimed to find out what young people, aged 16 -18, thought about being taught about climate change. Previous research has suggested that young people could find the issue of climate change upsetting, so the project also aimed to look at their emotional responses to the topic. The study involved young people taking part in a group discussion about their experiences of being taught about climate change and how they think the topic could be taught in the future. After the discussion they put their ideas about how climate change could be taught in the future into a mind map. Twenty-five young people from colleges in Greater Manchester took part in the study. There were three focus groups held, with between eleven and six participants in each. After the focus group the researcher made transcripts of the discussions by listening to a recording of the focus group and typing up what young people said, without attempting to ‘correct’ their language or grammar. Then the researcher carefully read all the transcripts and mind maps to become familiar with what had been said. Then these were coded, which involves going through the documents line by line and summarising the meaning of each line. Codes which had a shared meaning were grouped together, for example codes that referred to role-models. These groups of codes were used to produce four themes to describe what the young people as a group had reported about their experiences of being taught about climate change. The findings showed that young people knew about climate change but that they had a complex relationship with the issue. Both college and media had provided them with information. However, this information was not deep, and the images shown in the media gave them a negative impression of climate change. They also saw it as a global problem, which they wanted governments to help tackle. Currently they did not think that governments were doing enough. Thus, they saw the problem as so large and negative that it was potentially overwhelming, to avoid this they generally chose not to think about it. Earlier research into teaching about climate change focused on making sure people knew about the problem. However, more recently, research has found that knowing about climate change does not cause people to make environmentally friendly choices. This study helps to understand why this might be. The young people in this study knew about climate change but chose not to think about it. Their choice not to engage was logical: they did not see any solutions to the problem so ignored it to avoid distress. This suggests that when young people are taught about climate change this information needs to be carefully delivered so that they believe that there are solutions and that they can participate in these. This study also indicated that, to support a more positive view of the problem, young people’s education needs to be supported by wider societal changes.

This research would be beneficial to teachers tasked with delivering CCE. Firstly, this study demonstrated the importance of acknowledging the information about climate change that young people absorb outside of the classroom, particularly the negative way that this information is presented. Secondly, these findings suggest that young people currently feel low levels of agency to tackle the climate crisis, but that activities that allow them to participate in solutions would be potentially beneficial to building this. Finally, this study highlighted the importance of young people’s engagement in climate issues being supported by their wider culture. This is relevant to colleges and schools as a whole community as it suggests that CCE would be more effective if supported by the institution making visible moves towards sustainability. Moreover, young people suggested that deep investment in climate issues may not be socially acceptable. Through careful intervention schools could play an influential role in shifting these norms. However, this study also indicates that young people judge climate change to be an issue that requires government intervention. The negative perception of the future, which contributed to young people’s disengagement, was magnified by their perception that the government was not responding to the issue. Thus, these findings are also of political relevance as they suggest a relationship between government’s response to the climate crisis and young people’s ability to engage positively with the issue. Given that this has the potential to impact young people’s mental health in the present and their long-term attitude to the issue, this dimension of the findings cannot be ignored.

Little Red Book(LRB) as a platform for extracurricular collaboration and digital social support for Chinese university students

- University

- Digital

- Survey

- Quantitative

- China

- Digital technologies

- Digital Learning

Social media is widely used and has many educational advantages in various types of organisations, including higher education institutions, and is considered a platform for university students to collaborate and perceive digital social support. The LRB is a widely used platform in China that receives little attention from the education sector. Little is known about which types of students use LRB for collaboration, how they collaborate, and how different modes of collaboration influence their views of digital social support. By creating structural equation modelling (SEM), this thesis uses a quantitative research approach to analyse the relationship between variables. I found three ways in which students collaborate in LRB using questionnaire data from 199 university students in China: information seeking, information sharing, and information co-creation. Students' characteristics, such as self-efficacy and interest, were positively correlated with the three types of collaboration, with higher self-efficacy being more willing to participate in co-creation and higher interest in learning being more willing to share information. In addition to information sharing, the other two types of collaboration were positively connected with students' perceived digital support.

These study's findings encourage future study by demonstrating that learning through social media promotes student collaboration and access to social support, and hence, the use of social media in education deserves additional attention and research.

Mainstream secondary teachers’ perspectives on the causes of challenging behaviour and their awareness of link to speech, language, and communication needs.

- Interview

- Qualitative

- Teacher

- Secondary

- Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND)

- Education and Language

Speech, language, and communication needs (SLCN) include difficulties related to all aspects of communication including fluency, forming sounds and words, formulating sentences, understanding others, and using language socially (Bercow et al., 2008). SLCN is estimated to affect 10% of children and young people (Bercow, 2018). Children with SLCN are more likely to present challenging behaviours than peers with typical language development (Yew & O’Kearney, 2013). Yet, SLCN may not be recognised in children and adolescents presenting challenging behaviour (Hollo et al., 2014). Previously undiagnosed SLCN is widespread amongst young offenders (Snow et al., 2015). As teachers manage behaviour daily, they need to be aware of factors that affect behaviour. However, only one study had considered if teachers believe SLCN may affect behaviour, and this took place in the US with preschool teachers (Nungesser & Watkins, 2005). In the UK, secondary school pupils are ten times more likely than primary pupils to be permanently excluded (Gov.uk, 2020). Therefore, this project focused on what secondary mainstream teachers perceive to be the causes of challenging behaviour and their awareness of the link between challenging behaviours and SLCN. Seven current mainstream secondary teachers and one secondary special needs teacher, who had previously worked in mainstream, were interviewed through Zoom. They were recruited to the study through social media rather than through schools to encourage them to speak freely about the topic. Transcripts of the interviews were analysed to look for patterns. Four themes were constructed: impact of home and local area; the indirect role of education systems on behaviour; role models and relationships; and the links between SLCN and social-emotional development. The impact of the home environment on behaviour is consistent with previous research (Wang & Hall, 2018). Similarly, the importance of the student-teacher relationship in behaviour has been previously discussed (Stanforth & Rose, 2020). Generally, teachers have been found not to consider school-based factors to affect behaviour (Wang & Hall, 2018), which was not the case in this project. Teachers believed the curriculum and ability grouping affected self-esteem and behaviour. As this was the first study to consider secondary teachers’ perceptions on SLCN and behaviour, the link that teachers made between SLCN and social-emotional development was a new finding. Teachers in this study showed limited explicit awareness of SLCN. However, they discussed relevant factors such as how pupils struggled to discuss feelings, how teachers used simple questions to help students explain incidents, and how students’ behaviour may show that they are unhappy or finding school-work difficult. This study supports the recommendation that more training on SLCN is needed for education professionals (Bercow, 2018) but would add that the link to challenging behaviour must also be shared. An increased presence of speech and language therapists in secondary schools is also recommended to help schools recognise SLCN and provide additional support for those displaying challenging behaviours.

School leadership could use this dissertation to improve the professional development they offer staff, ensuring awareness of the link between SLCN and behaviour. With increased awareness that SLCN may accompany challenging behaviours, schools and teachers are more likely to arrange for assessments from SLTs and implement SALT programmes. SALT has been reported to improve confidence, communication, and behaviour in YOs (Snow et al., 2018) and similar outcomes could be expected for school students. As challenging behaviours can cause disruptions in learning for peers (Gregg, 2017), SALT could improve outcomes not just for students displaying behaviours but also for others in the class. The findings of this study could be used by universities to improve their teacher training by including content on SLCN and behaviour. Understanding students’ additional needs has been found to impact how teachers appraise behaviour (Hart & DiPerna, 2017) and teachers with less experience have been found to be more likely to engage in exclusionary practices (Stanforth & Rose, 2020). Thus, including SLCN in teacher training may support inclusionary practices amongst teachers who are new to the profession. Finally, the findings of this dissertation may empower parents to seek more support and assessment from schools if their children are displaying challenging behaviour. If parents are more aware of factors that may cause challenging behaviour, they can push for schools to provide the correct assessments and support. This would subsequently improve the wellbeing of students displaying challenging behaviour.

Mindfulness and psychological wellbeing among university students in the UK: The mediating role of emotion regulation

- University

- Mindfulness

- Student

- Survey

- Quantitative

- Wellbeing

- Education and Language

“Navigating Meritocracy”: Exploring the Influence of Meritocratic Beliefs on University Students’ Mental Well-being within the Context of Educational Involution in China

- University

- Qualitative

- Wellbeing

- Higher education

- Meritocratic beliefs

- Semi-structured interviews

- Reflexive Thematic Analysis

- Students

This dissertation aimed to understand how the common cultural belief that “hard work leads to success” (known as meritocratic belief) affects the mental well-being of Chinese university students. In today's China, students face an extremely competitive environment, often called “involution”, where they feel they must put in more and more effort yet fail to gain proportional reward. This study explored the impact of meritocratic beliefs on university students’ mental well-being within the context of involution in China, and the strategies they use to navigate the challenges. The research focused on students who have deeply experienced the Chinese culture and education system. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with nine Chinese postgraduate students and recent Master’s graduates. Although undergraduate voices were absent, participants’ reflective accounts provided a valuable perspective on how their beliefs and experiences developed over time. The interviews were conducted in Chinese via Zoom online meeting, and then transcribed anonymously. Reflexive Thematic Analysis was used to analyse the data, generating five themes that illustrated the ways in which meritocratic beliefs are internalised and navigated. The findings showed that meritocratic values were deeply ingrained in students’ upbringing through family practices, school systems, and broader cultural expectations. This contributed to what participants described as a “good student mindset”, characterised by perfectionism, fear of failure, and constant peer comparison. Such pressures often led to cycles of stress, diminished self-confidence, and identity anxiety. Furthermore, participants reported that the old rule of “hard work leads to success” is no longer true in the context of involution. Against economic changes and intensified competition, they found that hard work doesn’t always pay off as it might have for previous generations, and academic diligence no longer guaranteed secure employment or upward mobility. This mismatch between belief and reality led many participants to experience heightened anxiety and loss of motivation. Despite these psychological challenges posed by meritocratic beliefs, participants developed coping strategies. Many chose to redefine success on their own terms, prioritising intrinsic goals such as happiness, personal growth, and meaningful relationships. Parental support played a critical role in this process, offering reassurance that their worth extended beyond academic achievement. However, despite having access to professional psychological services, many students were reluctant to use them, believing that counselling couldn't solve their practical problems and seeing stress as a normal part of life. This created a crisis-oriented approach to mental health, where support was only sought at breaking point. These findings align with and extend existing psychological theories. They show how multilevel environments shape personal beliefs and how the frustration of basic psychological needs can harm motivation and well-being. In conclusion, the dissertation demonstrates that while meritocratic beliefs motivate students to work hard, they can also undermine mental well-being when personal worth is narrowly attached to academic achievement. Recommendations include broadening the discourse to value diverse forms of success, promoting proactive and culturally sensitive mental health support, and encouraging institutions to normalise help-seeking behaviours.

This research provides significant implications for families, educational practitioners, and higher education institutions in improving students’ mental well-being. The primary beneficiaries of this study are university students, particularly in China and Chinese international students abroad, who may feel trapped by meritocratic pressures. By validating their experiences, the research can help reduce feelings of isolation and encourage help-seeking behaviours. Furthermore, parents and families can benefit by gaining a deeper understanding of how their well-intentioned expectations might inadvertently contribute to their children’s psychological distress. This knowledge can empower them to provide more balanced support that prioritises holistic well-being over purely academic success. At the educational and institutional level, the findings are highly relevant for schools, universities, and educational practitioners. University administrators and counsellors can use these insights to develop more effective, culturally sensitive mental health interventions. This may involve implementing proactive outreach programmes to identify at-risk students and de-stigmatise psychological support. The research also provides a strong evidence base for policymakers in higher education to promote student well-being by valuing diverse talents, supporting extracurricular activities, and providing opportunities for personal development outside the classroom. Overall, this research contributes to a more critical sociocultural discourse about the balance between academic achievement and mental well-being, offering practical guidance for creating more supportive, inclusive, and healthy educational environments.

Navigating The Complexities Of Data-Trace Ethics In Education: A Study Of Secondary Teachers' Decision-Making When Using Apps In Classrooms

- Interview

- Digital

- Qualitative

- Policy

- Data and Rights

- Perspectives

- UNCRC

This study examines secondary school teachers' beliefs and perspectives on data-trace ethics when integrating apps into their classroom teaching routines. The literature review revealed that the digitalisation of education has accelerated the extraction and manipulation of children's data. While educators and schools adopt new technologies, they often fail to understand EdTech's ability to extract data and related ethical implications. This knowledge gap influences their ethical adoption of technology. The research is foregrounded in the UNCRC framework, recognising the unique and universal rights of vulnerable children that teachers must protect. The research employed in-depth semi-structured interviews and a focus group with 6 secondary school teachers. The interviews focused on classroom technology use, educators' beliefs on data-trace ethics, and how these beliefs influenced their practices. The findings revealed that the educators' reasons for adopting apps aligned with established technology adoption models. Educators held mildly negative views on data extraction by firms and displayed limited awareness of the data types extracted. They showed diminished personal responsibility regarding data-trace ethics, relying on institutional accountability and showing implicit trust in institutionally imposed technologies. Feelings of futility were prominent, stemming from perceptions of the overwhelming scale of the data being extracted by commercial firms and due to perceptions of the school and children's practices regarding data privacy. The study supported conclusions from previous research concerning educators' limited awareness of data extraction's consequences.

The study's findings highlight the urgent need for educators to understand data extraction techniques and institutions' roles in supporting this. The 'iceberg' model developed in this study offers a potential scaffold for this understanding. Concerns are raised in this research regarding observed apathy to online privacy, and further research exploring this is proposed. Other recommendations include exploring school leaders' perspectives and continuing to explore educator perspectives across more diverse settings.

Parental Math Talk and Children’s Numeracy Performance: The Mediating Effect of Spatial Language Comprehension and the Moderating Effect of Sex

- Student

- Quantitative

- Parent

- Mathematics

- Language

- Education and Language

Mathematical language comprehension is a term used to refer to children’s understanding of the spatial (such as “next to” and “above”) and quantitative (such as “fewest” and “more”) relationships between two or more objects. We know that parental math talk, or the mathematical language a parent/carer uses during interactions with their children, can improve children’s mathematical language comprehension. We also know that children’s mathematical language comprehension is related to their numeracy performance between 3 and 5 years old. However, we do not know whether children’s understanding of spatial or quantitative words has a larger contribution to their numeracy performance. This is important to study because it will help psychologists to make interventions that can improve children’s numeracy skills at home. For this reason, our study looked into whether parental math talk can lead to better numeracy performance, because it increases children’s spatial language comprehension skills. Our study also looked into whether this link had a larger impact on male or female children aged between 3 and 5 years old. We asked headteachers and nursery managers to forward an email to parents/carers of children who attend their primary school or nursery. The email contained information about the study and a link to the online questionnaire. We also posted a QR code on social media platforms that parents/carers could scan to access the questionnaire. Once parents/carers had read the electronic participant information sheet and had agreed to take part, they were asked for information about their child’s sex and age in years. The main study asked parents/carers questions about how often they use math talk with their child (10 questions), as well as about their child’s spatial language comprehension (28 questions) and numeracy performance (7 questions). Our sample included 370 parents/carers of children aged 3 to 5 years old who had no diagnosis of a developmental disorder. Of these, 180 children were male and 190 children were female. We found that parents/carers who used more parental math talk were more likely to have children with better numeracy performance than children who had heard less parental math talk. We also found that parents/carers who used more parental math talk were more likely to have children with better spatial language comprehension, and importantly, these children were more likely to have better numeracy performance than those with lower spatial language comprehension. This means that spatial language comprehension is one reason for how parental math talk is linked to numeracy performance in children aged 3 to 5 years old. Surprisingly, parental math talk had a larger impact on spatial language comprehension for children who were male than female. Our findings therefore build on earlier studies by showing that parental math talk may improve a specific part of children’s mathematical language comprehension: spatial language comprehension. This, in turn, may improve children’s numeracy performance between 3 and 5 years old. These findings provide important recommendations for educational psychologists who want to come up with ways to improve young children’s numeracy skills at home. For example, they could focus on increasing how much parents/carers use mathematical language during conversations with their children as this might help to improve their spatial language and numeracy skills. This is important as children with poor numeracy skills at the beginning of primary school are more likely to have poor numeracy skills in secondary school.

Given our significant findings, the current research has shed light on one mechanism that underlies the association between parental math talk and numeracy performance between 3 and 5 years old: children’s spatial language comprehension. This has important benefits for educational psychologists, who may consider spatial language comprehension as a potential mechanism to be targeted in early home-based numeracy interventions. These interventions may be particularly beneficial for females, who are often exposed to less parental math talk, and are therefore at risk of lower numeracy performance than males in primary and secondary school. Due to the challenges of engaging in conversational math talk throughout the school day, teachers and nursery practitioners could inform parents/carers about the longitudinal impact of one-to-one math talk on children’s numeracy performance, and advise them on the direct and indirect numeracy activities that they could offer to their child within the home environment to meet their particular needs. This will support the development of foundational numeracy skills that children will continue to build on throughout their formal education. Although further research is necessary, parents/carers of older children who are below the expected level in numeracy may also benefit from an increased exposure to parental math talk at home, by supporting them in reaching their academic targets. Longitudinal research could also identify those at risk of poor numeracy performance and whether these interventions are effective as a preventative. It is possible that these changes will have a lasting societal impact by reducing the underrepresentation of females in STEM courses and careers.

Perceptions of Teacher-Student Relationships Predict Reductions in Adolescents’ Distress Via Increased Trait Mindfulness

- Teacher

- Survey

- Quantitative

- Adolescent

- Education and Language

Stress is common in secondary school pupils, with high stakes exams, perceived pressure from teachers and parents, homework and tests, all featuring high on the list of common stressors for adolescents. The aim of this research was to understand how positive, emotionally close relationships with teachers can help reduce stress levels in pupils, by promoting the development of trait mindfulness skills. As opposed to trained mindfulness, trait mindfulness refers to an individual’s natural tendency to be mindful. It is believed to consist of four components: awareness (the ability to maintain attention on what is currently happening without being distracted by other events, thoughts and feelings), describing (the ability to use language internally and externally to label the experience), nonjudging (the ability to accept inner thoughts and feelings without worrying or self-blaming), nonreactivity (the ability to accept stress as a natural part of life, and actively detach from negative thoughts). This research aimed to provide new knowledge about how these abilities can be fostered and developed in the school environment. The target population was pupils in Years 9 and 10. This age group was selected as stress increases with age and proximity to exams. These year groups are preparing to sit their GCSEs and may therefore be experiencing heightened stress levels. Pupils this age are also going through an important developmental stage as they become more independent and autonomous. At this time, relationships with parents can suffer, and teachers may become more important as stable, adult, nonparental role models. This was therefore an ideal time to investigate whether positive relationships with teachers can help maximise pupils’ trait mindfulness skills, and in turn buffer their stress levels. The sample in the study comprised 124 pupils from two schools in the North West of England – an independent girls’ school, and a boys’ selective academy converter. Pupils in these schools came from affluent areas and achieved above the national average in KS4 results. Participants completed a short tick 65 box style survey designed to measure how they felt about their relationships with teachers in their school, their levels of trait mindfulness, and how often they have experienced stressful thoughts and feelings over the previous month. The research found that pupils who felt they had more positive, emotionally close, and supportive relationships with their teachers, were also more likely to have higher levels of trait mindfulness skills, in particular the components of awareness, describing and nonjudging. This was expected as adolescents who have supportive and close relationships with other adults in their lives, namely parents and other family members, also have higher levels of trait mindfulness. The findings also underline the important role that teachers play in adolescents’ psychological development. Pupils with higher levels of trait mindfulness, particularly awareness, describing and nonreactivity, also had lower levels of distress, suggesting that implementing strategies that foster these skills could be effective in reducing stress in school pupils. It was expected that pupils with high levels of awareness and nonreactivity would experience less stress, but it was not expected that the ability to describe a situation and label emotions would be linked to lower stress levels. This suggests that younger adolescents may use different skills when faced with potentially stressful situations, compared to older adolescents and adults.

The research provides new insights into the importance of relationships with teachers as a tool to maximise trait mindfulness skills in pupils, and how pupils utilise these skills when faced with potentially stressful situations. Mindfulness based stress reduction programmes, which teach mindfulness skills, are popular, but results are mixed. The theory behind using mindfulness for stress reduction is that if an individual is able to maintain their focus on the present, and observe and accept a potentially stressful situation and their response to it, they can avoid worrying about past or future events, and respond in a 66 measured way rather than resorting to knee-jerk reactions. This might mean pupils focus on revising for an exam, rather than worrying about the specifics of what might be in the paper, or the results of a previous test. However, while mindfulness training has been found to help reduce stress levels among pupils in the short term, without continued practice the benefits often wear off. The current research suggests that a simpler way for schools to promote mindfulness skills may be through fostering the innate abilities of their pupils to be mindful. These innate abilities are strongly related to the quality of relationships that pupils have with their teachers, and are also important for stress reduction. A focus on nurturing positive relationships between staff and pupils to promote trait mindfulness skills, in particular the components of awareness and describing, could therefore be effective in reducing stress in this age group.

Postgraduate Students’ Perceptions of the Impact of Emotion Regulation on Academic Transition in UK Higher Education

- Student

- Transition

- Emotion

- Higher education

- Education and Language

This study investigates the academic and social challenges international PGT students face during their academic transition and their ER strategies. Using a qualitative research method to obtain rich and in-depth data, it targets international postgraduate taught students, a significant but often overlooked cohort in UK higher education. These students face difficulties adapting to the UK educational system and social norms, compounded by being away from their families for the first time, thus highlighting the multiple multi-dimensional transition for international students. After recruitment efforts, ten participants were identified: nine from the SEED, one from the School of Engineering, nine from Asia and one from Africa. Data was collected via online semi-structured interviews lasting up to an hour, allowing for flexible scheduling and in-depth responses. Inductive thematic analysis revealed themes of academic study challenges, social challenges, ER strategies, and related subthemes. This study found that international PGT students face challenges in critical thinking, academic writing, using specific digital tools, adapting to fewer teaching sessions and independent study, student-centred teaching methods, and group study. Socialisation difficulties include language barriers, adjusting to low power distance with teachers, unfamiliarity with British social norms, discrimination, and establishing friendships with domestic students. Participants used cognitive change strategies, situation selection, and attentional deployment to cope with these challenges. While most findings align with previous research, this study found that situation selection, cognitive change and attentional deployment could also be effective even after emotions are triggered, contradicting Gross’s ER process model. Due to the limitations of the sample diversity, future research should include participants from a broader range of ethnic backgrounds to obtain more comprehensive insights. Additionally, due to the recruitment limitations and lack of member checking, future studies should ensure member-checking implementation to enhance data reliability. Future research should also investigate the financial difficulties faced by international PGT students to understand their academic and emotional challenges better, considering the significant tuition fees, visa costs, and limited scholarship opportunities.

Critical implications for UK higher education institutions include offering mandatory preparatory courses on critical thinking and academic writing before PGT programmes begin, informing students about required digital tools and general assessment timelines in advance, providing guidance on group discussions and group work and also academic staff should intentionally organise group work with both international students and home students. Social support should extend beyond welcome week, with continuous activities and mentoring programmes pairing international and domestic students. For ER, universities should engage former international students in interactive sessions and develop a year-long course on ER available to international students. Additionally, counselling services should be emphasised during welcome week, with faculty introducing these services during orientations. The main stakeholders who will benefit from this research will be future international PGT students and UK higher education institutions. International PGT students will have improved academic readiness through compulsory preparatory courses in critical thinking and academic writing, easing their initial transition. They will also benefit from early information on required digital tools to aid their preparation and academic performance. Moreover, advice on participating in group discussions and collaborative work will enhance their engagement and academic outcomes. For UK higher education institutions, ongoing social support and mentoring programmes will boost student satisfaction and retention rates. Additionally, offering long-term support programmes on ER and emphasising counselling services will support students’ mental health, fostering a healthier student body. Implementing these methods will also strengthen the institution’s reputation as a supportive environment for international students, making it more attractive to future students globally.

Practitioner’s Experiences And Perspectives Of Supporting The Social Media Use Of Young People In An SEN Setting And Its Effect On Wellbeing

- Education

- Wellbeing

- Education and Language

- Digital technologies

- Digital Learning

- Perspectives

The dissertation looks at how staff in SEN schools support students with their SMU and how SM impacts student wellbeing. Social relationships can be difficult for students in SEN settings, and their lack of understanding and exposure could leave them vulnerable, so the potential for SM to be a positive or negative could be higher. To explore this, seven teachers and TAs, two men and five women, from SEN settings in the North of England took part in one-to-one interviews over zoom and answered questions around the research aims. The findings from these interviews highlighted that those working closest with SEN students generally saw SMU as a negative thing, rather than a positive, which mirrored other work in the area. The content of SM, particularly the problematic things, like cyberbullying and inappropriate content, were talked about and their impact on students wellbeing. This opened up the question of how to decide if content is appropriate for the user or not, and whether or not SEN students are sheltered, which could make their SMU more difficult. The key resources participants used to support students were their strong relationships with the students they worked with. They reported a range of different support being offered to students, and relationships with staff were key which is a strength for SEN schools, which normally have much smaller staff to student ratios. All the participants talked about the need for more support for parents, and discussed the challenges parents face supporting and protecting SEN students in the digital age. They talked about the responsibility of SM platforms to protect their users and have better controls to help protect more vulnerable people, including those with SEN.

This research has real world applications as it highlights a need for more comprehensive SM training for school staff, to help them understand the positives and negative of SM and help them stay aware of the latest platforms, to allow them to best support students. During teaching and learning, the practicalities of staying safe and using technology and the internet should be integrated with more social education around positive online relationships. It may encourage teaching staff to reflect on their own opinions on SM and consider whether they are colouring their practice, and preventing SEN students from fully engaging with the SM world they are living in. It is useful to guide parents to reflect on the level of control they have over their young person’s SMU, and to decide if it is enough, too much or not enough. It demonstrates the need for more parental support, and possible changes to policy to ensure schools and parents are working together to keep everyone as informed as possible. The study has potential to effect legislation for SM platforms to provide a safer version of apps, which are restricted, to help protect more vulnerable users, or implement a system where users have to show competence and understanding of how a platform works before they can set up accounts. This would mean users on a platform have a basic understanding of what they have signed up for

Primary teachers’ perspectives: How is the emotional well-being of SEN children promoted and supported through interventions in UK primary schools?

- Teacher

- Primary

- Wellbeing

- Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND)

- Education and Language

This qualitative research project aimed to discover how EWB of SEN children was promoted and supported through interventions, within mainstream primary schools. EWB, is a complex multi-dimensional aspect of well-being which relates to self-esteem, self-reliance and self-efficacy. For this project, EWB has been defined as crucial for children’s emotional health, happiness and functioning. Over recent years, the UK government has advocated for improving EWB by developing children’s social and emotional skills, to buffer against emotional dysregulation and dysfunction. More specifically increases in numbers of children with SEN attending mainstream primary school, has coincided with a decline in well-being. Educators have identified these children are showing increases in maladaptive behaviours resulting in inattentive outbursts within the classroom. Yet, these psychophysical behaviours are indicators of dysregulation which affect EWB. Therefore, this project aimed to identify how teachers perceived interventions as promoting and supporting SEN children’s EWB.Considering this educational climate, the target population of teachers were selected to provide detailed insights from their experience of delivering interventions in everyday practice. Following liaison with several primary schools, teachers with five or more years mainstream teaching experience were selected from diverse socio-economic regions, across the Northwest. All teachers consented to take part in an online semi-structured interview which consisted of 13 questions related to the three research aims. Semi-structured interviews and a flexible interview style, allowed topical trajectories to be probed to develop insightful lines of inquiry. Data collected from interviews was systematically coded using the analytical process of thematic analysis. Patterns in the data were abductively coded and interpretated using themes from literature and the data with three main themes identified: intervention implementation and delivery, emotional regulation and staff knowledge and experience. Further review of the data enabled three subthemes for each theme to be established.Historically research has shown that universal interventions are crucial for developing children’s emotional and social skills. However, findings from this project have more specifically illustrated that both interventions support the development of SEN children’s higher cognitive (e.g: evaluation) and language skills required for emotional regulation, competence and awareness, key components of EWB. Interestingly, participants observations revealed that targeted interventions when purposively adapted had sustained a greater impact for reducing maladaptive behaviours. Yet the success of both interventions was interdependent on external factors of adoption, cost and fidelity, which influenced the delivery and implementation in practice. Overall, these findings bridge a gap between policy and practice, providing insight into how interventions provide therapeutic and preventive support, to buffer against emotional dysfunction. Therefore this project makes several recommendations, that interventions are purposefully applied to ensure that SEN children can receive consistent and sustained EWB support. To ensure educators make informed implementation and delivery decisions, compulsory government backed-training should be introduced. More specifically, this training should provide SEN specific guidance recommending how interventions could be adapted for diverse SEN children. Additionally, adopting a selection criteria would support teachers to make informed decisions regarding how to effectively deliver interventions. This would ensure that SEN children are accurately identified for a specific intervention and school-based outcomes. Thus, fulfilling wider policy requirements for a child’s needs to be met, continuing to make age-related progress alongside their peers.

This project has implications for educational research, UK educational policy and practice. It provides insight into how interventions can be used purposefully as therapeutic and preventative strategies, to support SEN children’s EWB. The project highlights that SLTs and SENCOs can drive policy change through implementing school-based intervention. Advancing this, the project acknowledges the importance of voicing teacher perspectives that provide crucial insights into SEN specific EWB needs. At the classroom level teachers can be essential agents of change, driving school and policy based decisions to improve EWB. Notably, the success and quality of this depends on teachers feeling secure in their knowledge and skills to purposefully adapt interventions to meet identified socio-emotional needs. Therefore, providing mandatory training on interventions specific to SEN, would develop a collective awareness of how to evaluate the effectiveness of school-based interventions to more accurately target EWB priorities.

Recognition, Identity, and Engagement: A Qualitative Study of the Cultural-Educational Role of Black Myth: Wukong among Chinese Players

- Interview

- Digital

- Culture

- Thematic Analysis

- Gameplay

- Heritage

This dissertation explores how Chinese players understand, feel, and learn from the cultural elements in Black Myth: Wukong, a 2024 Chinese action role-playing game adapted from Journey to the West. Existing research often focuses on Western-developed games, leaving a gap in understanding how domestic players interpret culture-rich Chinese titles. This project aims to fill that gap by examining how cultural recognition, emotional identification, and informal learning take place during gameplay. The study involved four Chinese participants, including two players who had completed the game and two non-players who were familiar with Chinese culture but had not played the game. The interviews explored three research questions (RQs): how players recognise and interpret cultural elements (RQ1); the emotional and identity connections they form (RQ2); and their willingness for further cultural exploration beyond the game (RQ3). All interviews were conducted in Mandarin to ensure accurate expression of cultural concepts. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, including live reactions to selected gameplay footage. The transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis, combining both deductive coding, guided by the “games-as-text / games-asaction” framework, and inductive coding to capture new insights emerging from the data. Findings show that players recognise cultural elements along two main pathways. First, some symbols trigger immediate recognition, such as Erlang Shen’s third eye, Zhu Bajie’s pig hooves, the Ruyi Jingu Bang, or traditional Chinese instruments like the xun and suona. These elements draw directly on shared cultural memory and are quickly identified. Second, other interpretations develop more gradually through gameplay, particularly when players must understand unfamiliar mechanics, follow complex boss narratives, or uncover the meanings of objects like the Root Bones. This reflects a “learning through doing” process similar to situated learning. Emotionally, players expressed strong feelings of nostalgia, cultural pride, and identity connection. Music like the Qinqiang opera scene or melodies from the 1986 Journey to the West TV series triggered childhood memories and cultural familiarity. The protagonist’s journey also evoked a sense of growth and self-cultivation, reinforcing identification with the hero figure. Finally, the study found that engaging with the game often motivated players to explore Chinese culture beyond the game world, such as researching myths, reading character backstories, or discussing design elements in online communities. However, this wasn’t true for everyone, showing that a game’s educational effect depends on the player’s own interests and background. Overall, the study concludes that Black Myth: Wukong can serve as both entertainment and a resource for cultural reflection and identity construction. Its educational value, however, is not automatic; it emerges from how players choose to interact with and interpret the game’s cultural layers. The research contributes a player-centred, qualitative understanding of how culturally embedded games are experienced by their domestic audience.

This research offers practical insights for multiple groups, particularly in cultural communication, education, and the creative industries. For general audiences, the findings show that commercial games can act as an accessible entry point into traditional culture. They can strengthen cultural confidence and reconnect young people with traditional stories, art, and music. Features such as opera, painting styles, and mythological symbolism can spark curiosity and encourage people to revisit their cultural heritage in modern contexts, thereby supporting meaningful cultural inheritance. For educators, the study highlights how digital games can support informal learning. Even when players do not intend to “study,” they still absorb cultural knowledge through exploration, interaction, and emotional engagement. This encourages teachers and educational practitioners to consider using culturally rich games as supplementary resources in courses related to literature, citizenship, or art appreciation. Even short gameplay clips or discussion-based sessions could help students connect classroom knowledge with lived cultural experiences. For the gaming industry and cultural institutions, the results emphasise the value of embedding cultural depth into design. Participants responded positively to authentic cultural cues, such as Qinqiang Opera and traditional design, and felt pride when these elements were presented confidently. This reinforces the idea that thoughtful cultural design, such as foreignisation strategies, authentic symbolism, and high-quality audiovisual elements, can increase both domestic acceptance and global visibility. Museums, cultural organisations, and content creators may also benefit from understanding how games can drive public interest in mythology, classical literature, and traditional arts. Finally, the research contributes to wider discussions on cultural dissemination. It shows that well-designed Chinese games can help counteract cultural discount and promote cultural diversity, suggesting digital games can serve as bridges between traditional heritage and contemporary media ecosystems.

Relationships between perceived parenting styles, global self-esteem, and academic procrastination in adult UK-based higher education students

- Survey

- Quantitative

- Parent

- Education and Language

This dissertation aimed to investigate parenting styles, self-esteem, and academic procrastination in an adult UK sample. Specifically, authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive parenting styles were studied. Authoritarian parenting is characterised by high levels of restrictions and discipline, and low warmth. Authoritative parenting is characterised by a medium-to-high amount of rules and restrictions, but high warmth. Permissive parenting is characterised by low rules and restrictions, and high warmth. Previous research suggests that the parenting styles used by one’s mother and father may influence one’s academic procrastination. Self-esteem is also believed to impact academic procrastination, and previous studies have found that individuals with low self-esteem are more likely to procrastinate. In the present study, it was hypothesised that self-esteem would be partially responsible for the relationship between parenting styles and academic procrastination. Gender differences were also investigated. 205 participants were included using online surveys. An independent samples t-test suggested that gender differences were only significant in paternal authoritative parenting. Men were significantly more likely to report authoritative fathers. Paternal authoritativeness was the only parenting style that negatively predicted academic procrastination in a regression model. Paternal authoritativeness was also the only parenting style that was significantly associated with self-esteem, indicating that the significant gender difference in paternal authoritativeness was potentially important. Because paternal authoritativeness was the only parenting style that was significantly predictive of both self-esteem and academic procrastination when other parenting styles were controlled for, it was the only parenting style included in the mediation model. The mediation model indicated that self-esteem does not significantly explain the relationship between parenting style and academic procrastination. Despite the gender differences in paternal authoritativeness, gender did not add any explanatory power to the mediation model. These findings differ from those of Pychyl et al. (2002) who found gender differences in this relationship. The different findings in the present study may be explained by the age of participants. The present study used adult (ages 18 to 49) participants, while Pychyl et al. (2002) used adolescent (ages 13 to 15) participants. Gender differences in self-esteem tend to lessen over time from adolescence to adulthood (Kling et al., 1999), which might explain why findings were different in an adult sample. Additionally, paternal permissive, maternal authoritarian, and maternal permissive parenting styles were positively and significantly associated with academic procrastination when other parenting styles were controlled for, in line with previous research (Batool et al., 2020; Zakeri et al., 2013). Future research should explore the potential roles of self-efficacy, self-regulation, and perfectionism in explaining the relationship between parenting styles and academic procrastination.

The findings of this study have real-world implications for interventions, parents, and future research. Much of the research on academic procrastination has focused on intrapersonal, rather than interpersonal factors (McCloskey, 2012). This study contributed to knowledge on the interpersonal impact of parenting styles on academic procrastination. Knowledge around the impacts of different parenting styles on factors like academic procrastination and self-esteem are important in informing parents and empowering them to make appropriate decisions that will benefit their children. The present study contributed to knowledge around academic procrastination by indicating that self-esteem is not the mechanism by which parenting influences academic procrastination in adult higher education students. This is relevant for informing academic procrastination interventions, which are currently under-researched, potentially due to the wide variety of correlates of academic procrastination (Zacks & Hen, 69 2018). The present study helped to clarify the relationship between two correlates of academic procrastination, which can inform future research on academic procrastination interventions.

Resilience in Education: Current Teachers' Perspectives on Key Factors Influencing Retention in UK Primary Schools

- Teacher

- Primary

- Wellbeing

- Emotion

- Education and Language

- Policy

- Perspectives

This study aimed to understand why teachers choose to stay in the profession despite many challenges. With many teachers leaving their jobs, this research identifies the key factors helping teachers remain committed to their careers. By exploring these factors, the study has been able to conclude strategies to improve teacher retention and support. Target Population and Sample The study focused on ten UK state primary school teachers, with a diverse mix of ages, genders, and teaching experience years. Their insights were crucial in understanding teacher retention. Method and Procedure To gather in-depth insights, the researcher conducted semi-structured interviews with the participants. These interviews allowed teachers to share their personal experiences and perspectives on the challenges and the reasons they stay in the profession. The interviews were conducted online, recorded, and then transcribed for analysis. The data was analysed using thematic analysis, a method that helps identify common themes and patterns in qualitative data. Findings and Literature Comparison The study identified four major themes: Workload and Professional Pressures: Teachers highlighted excessive workload, including lesson planning, marking, administrative tasks, and preparation for inspections, as major stressors. These tasks often lead to physical and mental exhaustion, affecting work-life balance. Coping Through Developing Resilience: Teachers use various strategies to cope with stress, such as exercise, mindfulness, and prioritising sleep. Support from colleagues and professional networks also plays a crucial role in managing stress. Positive Impacts and Personal Fulfilment: The intrinsic rewards of teaching, such as the positive impact on students and personal satisfaction, are significant motivators for teachers. They value the role they play in shaping students' lives and find fulfilment in their professional efforts. Commitment to the Profession: Teachers' commitment to their educational values and the sense of duty towards their profession are strong protective factors. Despite the challenges, their passion for teaching and belief in its importance keep them motivated. Summary Conclusion and Recommendations The findings suggest that financial incentives alone may not be sufficient to retain teachers. Instead, improving working conditions, providing strong support systems, offering professional development opportunities, and promoting a positive school culture are crucial. These strategies can help alleviate the stressors teachers face and enhance their job satisfaction and retention. The research underscores the complex nature of teacher retention, revealing that a combination of systemic, professional, and personal factors influence teachers' decisions to stay in the profession. Despite the widespread challenges, teachers remain committed due to intrinsic motivations, such as positive impacts on students and their passion for teaching. The findings challenge the idea that financial incentives are the primary solution for retaining teachers. While competitive salaries are important, they are not sufficient on their own. Teachers highlighted the need for a supportive work environment, manageable workloads, opportunities for professional development, and recognition of their efforts as crucial elements that contribute to their job satisfaction and decision to stay in the profession. By focusing on these areas, schools and policymakers can create a more supportive and sustainable teaching environment. This approach not only benefits teachers but also enhances student outcomes and overall school performance by fostering a stable and experienced teaching workforce. By implementing the recommendations of this dissertation, schools and policymakers can create a more supportive and fulfilling work environment for teachers. This approach not only addresses the immediate challenges faced by educators but also promotes long-term retention, leading to a more stable and effective education system. These strategies are designed to ensure that teachers feel valued, supported, and empowered to continue making a positive impact on their students' lives.

Potential Benefits and Stakeholders The research has real-world applications and could benefit various stakeholders, including: Schools and Educational Institutions: By implementing the recommended strategies, schools can create a more supportive environment for teachers, reducing attrition rates and improving educational outcomes. Educational Practitioners and Policymakers: The findings provide valuable insights for developing policies and practices that support teacher well-being and retention. Teachers: Enhanced support and professional development opportunities can improve job satisfaction and reduce burnout, contributing to a more positive teaching experience. Students and Parents: Retaining experienced teachers can lead to more stable and effective learning environments, benefiting student achievement and overall school performance. The General Public: Understanding the challenges and motivations of teachers can foster greater appreciation and support for the teaching profession, promoting a positive societal attitude towards education. The impacts of this research could include: Educational: Improved teaching practices and teacher retention can enhance student learning outcomes and overall school performance. Societal: Greater awareness and appreciation of the teaching profession can lead to more robust community support for teachers. Cultural: Promoting a positive school culture and valuing teachers' contributions can foster a more supportive educational environment. Policy and Practice: The findings can inform the development of policies that address teacher workload, support, and professional development needs, leading to systemic improvements in education.

School belonging in students with SEND: Perspectives of secondary school staff

- Interview

- Student

- Education

- Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND)

- Education and Language

- Digital Learning

This study sought to understand the experiences of educational professionals in relation to the development of school belonging in students with SEND. The principal research questions for this project were: RQ1: How do secondary school staff promote school belonging in students with SEND? RQ2: What are the identified barriers to development of school belonging for students with SEND? The research’s target population was mainstream secondary school staff across four LAs within the CGMA who had sufficient experience working with students with SEND. The participant sample consisted of seven participants, four male and three female, from four LAs within the CGMA. Their schools reflected student population sizes ranging from 800 to 1300, and measures of deprivation from 1st to 7th Index of Multiple Deprivation decile. The study received ethical approval from the University of Manchester Ethics committee (Appendix F) and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All identifying participant information was removed from transcripts and participants were referred in accordance with identification codes which are used in Chapter 3 to evidence quotations. The research used semi-structured interviews conducted online via Zoom. Interviews took place across a period of 24 days, with each interview lasting between 48 and 70 minutes. Interview audio was recorded for transcription purposes, before being securely deleted from encrypted storage. Nvivo-14 was used to host the dataset and support organisation of analysis. The data were coded with a hybrid approach using reflexive thematic analysis without attempting to shape it into pre-existing frameworks. Analysis was guided by Braun and Clarke’s (2013; 2022) recommended steps to reflexive thematic analysis. The research took a constructionist epistemological approach in assuming that data is influenced by those active in the research process, including researchers and participants (Willig, 2022). This study took the Big Q approach to data interpretation, acknowledging the role of the researcher in determining what the data represents in terms of themes (Braun & Clark, 2013; Willig, 2022). From a constructionist paradigm, the data were analysed with the aim of understanding the complex world of lived experience from those within it (Mertens, 2020; Schwant, 1994). Data were analysed as a process of meaning making, rather than of truth seeking, in accordance with the study’s epistemological position. Findings highlighted school staff efforts in promoting feelings of school belonging for students with SEND. Two key themes were central to this: acceptance and identity, and culture, community and relationships. Staff attitudes and trusting relationships were found to be particularly influential in determining the school’s culture of inclusion and belonging for those with SEND. Feeling safe in school was also recognised as crucial to fostering school belongingness. Participants reflected on barriers to the development of school belonging for students with SEND. These barriers were primarily rooted in resource demand challenges, both on the school and LA level, which limits access to sufficient and appropriate SEND provision. Findings also indicated that an evolving landscape in terms of SEND identification and increasing student need was an additional barrier to school belonging. This study’s findings broadly align with pre-existing literature on the topic of school belonging for students with SEND. Perhaps most noteworthy to consider alongside this study’s findings is Allen et al.’s (2016) socio-ecological framework of school belonging (Figure 1) which uses Bronfenbrenner’s EST (1979) as a basis for understanding how students develop a sense of school belonging. These findings build upon pre-existing definitions of school belonging to include recognition of deep connection with trusted adults, alongside connection with social groups, physical places and individual collective experiences (Allen et al., 2021). The barriers to developing school belonging identified in this research are also consistent with earlier findings, particularly in relation to the influence of staff training, staff attitudes and teacher-student relationships (El Zaatari & Maalouf, 2022; Mulholland & O’Connor, 2016; Pit-ten Cate et al., 2018). These findings indicate the importance of staff competency and confidence in recognising SEND-related behaviour and responding to this appropriately, which echoes pre-existing discussions regarding the usefulness of behavioural sanctions and the value of suspensions and PEx as a behaviour management strategy (Allen et al., 2021; Lehane, 2016; Pyne, 2019; Williams et al., 2018). This study reiterates the importance of staff attitudes and stakeholder relationships in enabling students with SEND to feel accepted and understood in their school setting. Findings indicate the pressures experienced by mainstream secondary schools in including students with SEND in school communities within day-to-day practice. This research raises further questions regarding how those with SEND can be supported to develop school belonging, given the identified challenges. Future research which sought first-hand student views would be particularly valuable to examine this.

The findings of this study can be applied to various stakeholders, perhaps most notably senior leadership teams, SEND staff and class teachers working in mainstream secondary schools. It also has relevance for LA professionals who closely liaise with mainstream secondary schools. This study could have tangible educational impact on inclusive practice, behaviour policy, alongside teaching and learning strategies to enable students with SEND to feel a sense of belonging within the classroom. These findings also indicate the need for reflection at the level of senior policy making in relation to the resource difficulties discussed and the long-lasting societal impact of this on the development of inclusive school communities, as called for by Salamanca (UNESCO, 1994) and the Warnock Report (Warnock Committee, 1978).

Seeing Sustainability: A Participatory Visual Study of Coffee Farmers’ Knowledge, Negotiation, and Aspirations

- Interview

- Qualitative

- Focus group

- Semi-structured interviews

- Sustainability